In the midst of the book reading and movie watching challenges

hereabouts, I decided to combine the two to write about one of my

favourite authors, whose small body of work has been the basis of, or

has influenced, some of my favourite films.

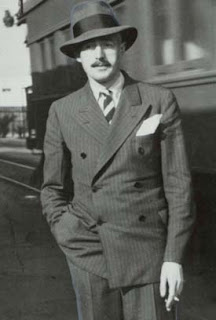

Dashiell Hammett wrote just five complete novels and a handful of

short stories. He wrote a new kind of detective fiction, drawing from

his own experiences as an actual private detective for California’s

Pinkerton Agency. The style became known as “hard-boiled” – lean

descriptions of ugly people in ugly places doing ugly things.

Sympathy was hard to find, but Hammett was careful to make his

anti-heroes just heroic enough – as cynical as things got, there was

always one guy willing to crack wise and (eventually) do the right

thing. And hopefully get paid for it.

I’ve broken my deranged rambling into two parts, for easier digestion.

The first covers the thematically-related Red Harvest (1929) and The

Glass Key (1931). The second will cover his most famously adapted

books, The Maltese Falcon (1930) and The Thin Man (1934).

1) ‘Red Harvest’ and ‘The Glass Key’

The Pinkerton Agency was notoriously involved in labour disputes and

strike breaking in the era that Hammett worked for them. This

experience informed his books Red Harvest and The Glass Key, two

novels with a number of shared elements, in particular the backdrop of

a small town being fought over by violent gangs and unscrupulous local

magnates.

Hammett had created a new type of detective fiction in his short

stories through the 20s, combining a flair for the drama of fiction

with the dour and seedy grit of his real life experience. His first

novel, Red Harvest, was the brilliantly executed culmination of this

period, and was a true watershed in crime fiction.

The protagonist is the Continental Op, the nameless actor in many of

his stories to date with whom he laid the template for the PI who lets

people believe he is more crooked than he really is. His client is

already dead by the time the Op reaches “Poisonville”, and he solves

that murder before fulfilling his contract to clean up a town riven by

violent factions, playing them against each other, even though at

times it seems like he is the only one who wants the town cleaned up.

If there are pieces of the story that seem familiar, that should not

be surprising, as many elements have been incorporated by future

storytellers. These include Akira Kurosawa and the Coen Brothers, but

although the influence of Red Harvest is clear on the films Yojimbo

and Miller’s Crossing, the filmmakers themselves identify the works in

question more closely with another Hammett novel, The Glass Key.

The Glass Key shares a similar storyline of a powerful local figure

attempting to hide behind, and profit from, criminal gangs, and a

smaller player pitting opposing sides against one another to quell

gang war. Miller’s Crossing, unfairly one of the more overlooked Coen

Brothers movies, is in part a very close adaptation of the book, but

there are a number of significant departures. They skillfully take the

core of Hammett’s story and adapt it where necessary to make the

result more characteristically a Coen Brothers film, something even

starker and more unsettling than the source material.

The Glass Key had already been adapted by Hollywood a couple of times

before. I haven’t seen the 1935 version but the more famous of the

two is the 1942 noir classic featuring an amazing Veronica Lake and

Alan Ladd. As with Miller’s Crossing, the makers of The Glass Key

were careful to make the material fit their ends, and in this case the

result is both a Hollywood movie of the era and an important

development in the budding noir genre. The former part of that of

course means that the plot is simplified and the politics are reduced

to the background in favour of the love story. Again though, the

license is taken adeptly, and the resulting film, while not a

completely faithful adaptation, is stronger for it.

The Glass Key is a wonderful film and well worth looking up. I was

very fortunate to be able to see in a cinema once and it remains one

of my favourite movie experiences. Miller’s Crossing is also very

much recommended. I have skipped over Yojimbo here but that film

certainly deserves its strong modern reputation, and of course it

endowed the influence it drew from Hammett’s novels on the several

notable films that were in turn influenced by it. A movie of Red

Harvest was made in 1930 which I have not seen, but which has a poor

reputation.

The books themselves are both very strong. Hammett had a gift for

devising involved plots and then executing them without confusion, and

that shows up in these novels more than any others. The characters

are typically boldly drawn and the action is paced and addictive. Red

Harvest in particular is considered perhaps Hammett’s finest work.

The author himself, however, cited The Glass Key as his favourite of

his own novels.

-Lee B.

No comments:

Post a Comment